The Church in Europe |

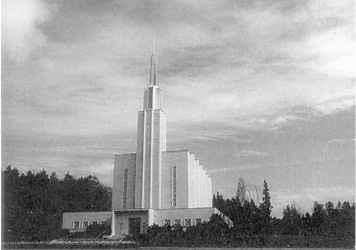

The Swiss Temple in Zollikofen (near Bern, Switzerland, 1978) was dedicated in 1955 by President David O. McKay, with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir participating. This temple, built of white reinforced concrete with gold spite, was the first outside the United States and Canada. Courtesy Floyd Holdman.

by Douglas F. Tobler

[This article discusses the establishment and growth of the Church in continental Europe. See separate articles on the Church in the British Isles, the Middle East, and Scandinavia.]

The Protestant countries of Western Europe—Scandinavia, Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands—played a major role in the growth and success of the Church from the beginnings in the 1830s until well into the twentieth century. Along with the United States, Canada, and Great Britain, continental Europe provided most of the early LDS converts until around 1960, when successes in Latin America and Asia began to overshadow it as a source of new converts. Without the waves of European converts, many of whom emigrated to fill up the pioneer settlements of the Great Basin Kingdom (see Colonization), the Church would, at best, have grown more slowly, been more insular and provincial.

That success in Europe was, however, geographically uneven. Early converts came overwhelmingly from the countries of the Protestant Reformation. Attempts were made as early as the 1850s to gain converts in France, Italy, Ireland, and Austria-Hungary, but results were meager and missionaries became discouraged. Real success in these and other Catholic countries would have to wait for the more open societies and attitudes of the twentieth century. LDS missionaries also found virtually no access to the Orthodox populations of Eastern Europe, whether in Russia, Greece, or the Balkans, and there were only a very few conversions of European Jews.

LDS converts came from many different Protestant denominations and sects, but most of them were religious "seekers" of one kind or another, sometimes already united in congregations like Timothy Mets's "New Lighters" in Holland in the early 1860s. Most of the seekers had studied the Bible and were looking for a church with apostles, prophets, and the spiritual gifts they had read about in the New Testament. They also tended to be discouraged with traditional doctrines and the behavior of churches and pastors, and longed for the assurance of communion with the spirit of God in preparation for Christ's imminent return.

Most European converts came from the middle, lower middle, and especially the working classes. One study which surveyed LDS immigrants to the United States between 1840 and 1869 found that only 11 percent were middle class, mostly artisans; the rest came overwhelmingly from the working classes. Early attempts were made by missionaries to interest such dignitaries as the queens and kings of various countries, but these appeals fell on deaf ears and sometimes even led to the missionaries' banishment. Their preaching also had little resonance with the traditional nobility, the moneyed aristocracy, and an increasingly secular and powerful intelligentsia. Thus, cut off from "respectable" society, they went "to the poor like their Captain of old" (Hymns, 1985, No. 319), among whom they found believers. Only in the later twentieth century, as they had done in America, did European Latter-day Saints as a group begin to be part of the growing middle class as they received greater opportunities for higher education and financial success.

The new European Saints of the nineteenth century came from both rural and urban societies. Farmers, agricultural workers, and artisans joined with industrial workers and townspeople leaving the depressed countrysides and the slums of industrializing Europe for the kingdom of the Saints in what they and thousands of other emigrants believed was the Promised Land, the land of unlimited opportunity.

Some three years after the Church was established in Europe, it introduced the doctrine of the gathering, which encouraged the new members to gather to Zion. Before 1900 more than 91,600 heeded the call, and although after the turn of the century Church authorities began to discourage emigration, thousands more joined the ever-broadening stream of European immigrants to America. They scrimped and saved, sometimes for years—the average wait was ten years—to get the eighty to one hundred dollars needed to get from Liverpool to Salt Lake City. Saints from the Continent went to Liverpool, where, with British converts, they booked passage on large emigrant ships, such as the Amazon, Nevada, or Monarch of the Sea. They first landed in New Orleans for the trip upstream to Nauvoo, later they landed at New York, Philadelphia, or Boston, traveled by train to Omaha, and then journeyed by covered wagon or handcart the remaining 1,100 miles to Utah. For some the trip was better than tolerable; for many others, it was an ordeal endured only through faith and determination.

Seeing that most new converts were so poor that they could not emigrate without help, the Church, in 1849, set up the perpetual emigrating fund which allowed thousands of Saints to borrow the money to emigrate and then repay the fund after they were settled in the American West. After the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, the journey was not so arduous because the railroad brought emigrants directly to Zion.

European LDS emigration peaked in the 1850s and 1860s, although a fairly constant stream, especially of Germans, continued after the turmoil of both world wars. They all became part of the "melting pot," with few Saints returning to their native lands.

The European members turned out to be exceptionally good pioneers. Most brought with them solid religious conviction and faith, an unusually strong work ethic, usable and practiced skills derived from the quality artisanship of Europe, and a desire to blend into their new society and surroundings. They also brought a deep respect for Church leaders as God's chosen servants, a willingness to settle where they were called, and a desire to help promote the missionary cause, especially in their native lands. They were persuasive recruiters of their fellow countrymen to the new LDS settlements. Many met incoming emigrant trains to take settlers to their new paradise.

Besides laborers and skilled craftsmen, there were also businessmen and entrepreneurs and teachers; there were women trained as midwives and a few as doctors. Europe also produced poets, journalists, artists, architects, photographers, musicians, and also dramatists. From their ranks arose a range of great leaders from General Authorities to missionaries—who usually labored in their homelands. Devout women and children who supported the Church, often at great sacrifice, carried out their own daily and Church duties. Most important, however, were the tens of thousands of less-known European Saints; Zion could not have done without them. Census figures give us some idea of their numbers. In 1880, out of a total Utah population of 143,863, almost 43,000, or 30 percent, were foreign-born. If children born in America to foreign-born members are included, the figure would exceed 60 percent.

Not all European converts to the Church immigrated to America, even in the peak years of the gathering. Some had families they could not and would not leave; others lacked faith and funds. Some drifted from the faith or could not find suitable marriage partners in it. Others succumbed to the extraordinary anti-Mormon pressures and persecutions that arose simultaneously almost everywhere with the arrival of the missionaries. Throughout Europe in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Latter-day Saints, and especially missionaries, were at one time or another harassed, abused, vilified, stoned, jailed, and expelled; yet these same missionaries were simultaneously fed, clothed, housed, protected, and warned by generations of grateful and admiring members. In the nineteenth century, the Church was taken seriously, perhaps too seriously, by those in power. Many Europeans regarded the Church as a non-Christian American sect. Throughout Europe, where the marriage of church and state had been sanctified by tradition, political authority often took its cues on religious matters from a clergy made more vocal by declining influence.

Prominent Europeans visited Utah to get a firsthand view of this unusual and exotic LDS society. They admired the way the Saints had made the "desert…blossom as the rose" (Isa. 35:1), but found the people fanatical and their theology incomprehensible. Polygamy was considered especially uncivilized by Europeans, who viewed their own culture, especially near the end of the nineteenth century, as the apogee of civilization. For the European intelligentsia, the LDS Church was purely and distinctly an aberrational American phenomenon.

In spite of all this, the Church took hold in Europe, at least enough to strengthen the Church in America when strengthening was needed most, and also to lay a foundation for its own existence later on. Following their great successes in Great Britain in the 1830s and 1840s, the missionaries crossed the English Channel to work on the European mainland. The responses in Switzerland and Hamburg, Germany, were generally positive, with a foothold established in each of these areas. Less successful were the missions of Lorenzo Snow in Italy and John Taylor in France, but even in those nations a few converts were made, from whom significant LDS posterities have grown. There was a slow but steady growth of the Church in Switzerland and Germany, especially after German unification in 1870. A mission was established in the Netherlands in the 1860s, and over the years thousands became Latter-day Saints and immigrated to Zion.

Results were not so encouraging in the huge Austro-Hungarian Empire of more than fifty million that sprawled over most of the map of East Central Europe. In 1865 President Brigham Young sent one of the apostles, Orson Pratt, to open that empire to missionary work. Elder Pratt and his companion, William Riter, had little success, spending most of their time in jail. A later missionary, Thomas Biesinger, made scattered converts in Vienna and Prague; and a Hungarian convert, Misha Markow, traveled throughout most of the Balkan states and Russia, beginning in 1903, performing isolated baptisms and encountering ubiquitous opposition.

At the same time, attempts were made to breach the edges of the Islamic world in neighboring Turkey. A Swiss convert, Jacob Spori, established a mission there in 1884 with limited success (see Middle East, the Church in). After Spori baptized some Russians, Elder Francis M. Lyman, an apostle, and Joseph Cannon dedicated imperial Russia to preaching the gospel in 1903.

TWENTIETH CENTURY. For Europeans, Church members included, the dawning twentieth century would bring historic and cataclysmic changes. These included two devastating world wars with literally millions of casualties and a debilitating depression in between, fascism and communism, the Cold War and Americanization, prosperity and the rebirth of Europe, and finally, by 1990, the extension of freedom and democracy to most of the people of the continent.

There were also significant changes in European LDS life. Emigration gradually declined, allowing the European population to grow and more permanent LDS congregations to emerge. New countries, first in the West, then later in the East, were opened to missionary work; and some, such as France, Belgium, and Italy, that had been opened but later closed, reopened and became more fruitful. Freedom of religion and the end of religious persecution spread as democracy overcame a variety of tyrannies. The discontinuance of polygamy and the accommodation to the broader palette of political realities in the world emphasizing the spiritual mission of the Church opened doors.

The defeat of Germany and the Central Powers in World War I, though viewed as a disaster for the people, did have a bit of a silver lining for the Church, especially in Central Europe. The coming of democracy to Germany and Austria permitted the return of missionaries. A vigorous branch was established in Vienna that would serve as a strong foundation for the Church in Austria. The rigors of war and defeat had produced a poverty and humility among the people that helped make them more receptive to the gospel message. Missionaries streamed into post-World War I Germany and, especially in the first years of the Weimar Republic, baptisms were at an all-time high. By 1930 there were more Latter-day Saints in Germany than in any other country outside the United States of America, and expectations ran high for continued growth.

The coming of Hitler to power changed life for the Church and its members, not only in Germany but eventually in the rest of Europe as well. Soon the omnipresent police state was making life in Germany more difficult for the Saints, especially the missionaries; many anticipated the Church would be closed down, but it never was. Both members and missionaries made every effort to get along with the regime while rejecting its excesses. What was important to them was to be able to continue to preach the gospel, to stay in the country, and to keep the branches together and prospering after so many years of struggle. Moreover, their numbers were small and they had little leverage with the regime. The Church grew slowly throughout Europe in the 1930s, and the growing tension in society made missionary work progressively more difficult.

In the fall of 1938, at the time of the Munich conference, missionaries were taken out of Germany temporarily; this became a valuable dress rehearsal for the situation a year later, when the Church was forced overnight to withdraw all missionaries from Germany and eventually from all of Europe. After European Mission President Thomas E. McKay left in April 1940, the local leaders of the Church units on the Continent were on their own throughout the war.

The cataclysm of World War II prompted Church leaders to send Elder Ezra Taft Benson to Europe in 1946 to survey the damage, find the Saints, arrange for temporal help, and, most important, let them know that the Church cared about them. Elder Benson found decimated but devout congregations of Saints wherever he went, from England to Austria. He lamented over their circumstances and was inspired by their devotion. He also arranged for them to meet, and he set in motion the wheels that would bring the welfare supplies that had been accumulating in America to the needy in Europe. Years later, members vividly and gratefully remembered this mission of mercy and found in it hope and encouragement to face a difficult future; one non-Mormon German professor recalled having received his first pair of shoes after the war from the Mormons. Soon help began to pour in as CARE packages of relief supplies arrived from friends and fellow Saints in America. The Saints in the Netherlands, which had been invaded and occupied by Germany, sent potatoes. Trainloads of welfare supplies were sent from Utah to needy Mormons and non-Mormons alike. It was a great expression of Christianity in action, and the image of the Church in Europe began to change for the better as a result of its participation in this collective humanitarian effort.

Missionaries began to return to Europe as early as 1946. Soon missions were reestablished and some mission presidents had to locate scattered Saints, but others found things intact. Members met where they could, sometimes in bombed-out quarters, sometimes in members' apartments, and sometimes out in the open. A new mission was also established in Finland in 1947. During the first decade after the war, efforts focused again on the traditional interests of strengthening the Saints and gaining new ones.

Prior to the war, European members had never been able to attend a local Church temple. Many had been diligent in doing genealogical research, but unless they had immigrated to the United States or had been able to visit there, they had not had the opportunity to attend a temple and receive the blessings given only therein.

But all this was to change dramatically. Members in post-World War II Europe soon acquired all of the blessings and responsibilities of Saints in America. In 1952, a year after he became President of the Church, David O. mckay announced plans to build the first temple in Europe just outside of Bern, Switzerland. This temple was dedicated in September 1955; a second one was completed and opened near London in 1958. The building of these temples symbolized the inauguration of the new age for the Church in Europe. In the 1980s, the Church dedicated a temple in 1984 at Västerhaninge (near Stockholm), Sweden; in 1985 at Freiberg, then the German Democratic Republic (GDR); and in 1987 at Friedrichsdorf (near Frankfurt), then the Federal Republic of Germany.

Some other important changes were the creation of new missions and the establishment of Europe's first stake in 1961. In addition, the progress of secularization, with its emphasis on freedom of religion, the ecumenical spirit of Vatican II in the Roman Catholic Church, and the presence of American LDS service personnel helped to break down the traditional prejudices and make it possible for the Church to gain a real foothold in Italy, and later in Spain and Portugal. New vigor was experienced in France as baptisms increased; membership in France grew from 1,509 in 1960 to 8,606 in 1970. Most significant was the conviction that it was now possible to do missionary work among the Catholics of Western Europe in the same way, and with as encouraging results, as among Protestants.

The Saints became not only more numerous but also more prosperous and better educated; Europeans such as F. Enzio Busche (Germany), Charles A. Didier (Belgium), Derek A. Cuthbert (England), Jacob de Jager (the Netherlands), and Hans B. Ringger (Switzerland) were called as General Authorities. Stakes, wards, and new missions were organized with leadership essentially in local hands; European LDS youth were better educated in Church doctrine through the establishment of seminary and institute classes; a new and larger wave of missionaries from Europe joined the worldwide force; and Central and Eastern Europe were, especially after the political revolutions of 1989, opening their doors to the Church.

In Europe the image of the Latter-day Saints and the Church was changing. The coming of real democracy, with its basic human rights, including the freedom of religion; the pervasive influence of the United States as the primary defender of an exposed Europe in the Cold War; the mobility and growing prosperity that came to Europe; and the continuing growth of the Church generally gave it a more favorable press.

At the same time, the deepening Cold War made life progressively more difficult for some seven thousand Saints in the GDR. Strong anticommunist rhetoric from America, plus Russian influence and strong communist prejudices against churches and people of religious conviction, brought Latter-day Saints behind the Iron Curtain continued surveillance and harassment. The erection of the Berlin Wall in 1961 left them largely to their own devices, with only occasional visits by Church authorities from the West. Some, in order to make their peace with the new order, withdrew from Church fellowship, but a majority banded together to form a strong, cohesive LDS community.

In the 1960s, the Church began a vigorous program of building chapels for European congregations that helped to meet the needs of the Saints as well as to gain some respectability in society. By 1970 chapels dotted the Western European landscape; they attracted some positive outside attention and gave members a new sense of accomplishment. They also helped Saints begin to shed the "sect" image and mentality and to move more confidently into their various national societies after years of persecution and disrespect.

In an attempt to strengthen the LDS European youth, the seminary and institute programs of the Church were established in the early 1970s. These would help LDS families teach their children the gospel and prepare them for missions and lifetimes of service. Gradually, an increasing number of young men and women did serve missions. The 1970s also brought area conferences at which the European Saints were able to see how many of them there actually were and to be counseled anew by Church leaders to remain where they were and help strengthen the Church in their own areas.

EASTERN EUROPE. Prior to the 1960s, LDS success in Europe had been confined largely to the Protestant countries of Western Europe. A few converts, such as Janos Denndorfer, had been made in Hungary around the turn of the century, and a few others later in Czechoslovakia, but the turmoil of the first half of the twentieth century and the dropping of the Iron Curtain around Eastern Europe effectively precluded the early introduction of the gospel and Church into those countries.

In the 1960s, attempts were made to begin missionary work in Yugoslavia, but it was not until Kresimir Cosic came to Brigham Young University, became a convert to the Church, and later was a basketball hero in his native country, that the Church could take hold there. A few missionaries were allowed to enter, but their opportunities to teach the people were circumscribed.

Vienna became the center of attempts by the Church to push into Central and Eastern Europe, much as it had been the capital of the polyglot Austro-Hungarian Empire of the nineteenth century. In the 1970s a few missionary couples were called to serve in Budapest, Hungary, and by the early 1980s they had established a branch comprised of more than one hundred capable, educated Hungarians. This gradual breakthrough almost exactly mirrored the gradual turning of Hungarian society and government away from the strict subservience to the Communist masters and toward the West.

For President Spencer W. Kimball, the need to preach the gospel everywhere in the world, especially in the large areas from which the Church had heretofore been excluded was a consuming passion. He had no political agenda. A major breakthrough came with the work of Ambassador David M. Kennedy in gaining official recognition of the Church in various areas and in the dedication of Poland for the preaching of the gospel by President Kimball in 1977. This represented a major change in Church policy toward communist governments and paved the way for even more significant opportunities in the late 1980s. It became the basis for a policy that allowed contacts with scattered Saints in Czechoslovakia and brought the Church recognition and respect from the communist leadership of the GDR, in all a breakthrough in that part of Europe. The most dramatic results of this changed relationship were the 1985 erection of the temple at Freiberg, GDR, wherein for the first time hundreds of lifelong Latter-day Saints were able to fulfill their dreams of temple worship, and the subsequent admission of LDS missionaries into the country for the first time in nearly forty years. In 1989 the first missionaries allowed to leave the GDR arrived in Salt Lake City to be sent throughout the world.

The nearly bloodless revolutions of 1989 presented the Church with an opportunity to begin a new epoch in Central and Eastern Europe. As the communist order crumbled and more democratic regimes were established in one country after another, one common demand was for freedom of religion. As a result, by the end of 1990 the Church in these countries existed under virtually the same conditions as in Western Europe and the United States. The reunification of Germany applied all of the rules of the Bonn Constitution to what had been the GDR. Missions have been established in Poland, Hungary, and Greece, and reestablished in Czechoslovakia. Leaders of these nations have welcomed Latter-day Saints because of their strong Judeo-Christian values and their wholesome families. Missionaries are currently proselytizing on a limited basis. Congregations of the Church have been officially recognized in the Soviet Union, and it has good prospects there, and in Yugoslavia, for the immediate future. Missionaries have been permitted into Romania and Bulgaria, the first significant breakthroughs in those countries. Thus, at the beginning of the 1990s, THE CHURCH of JESUS CHRIST of Latter-day Saints in Europe stands on a new threshold. Its major challenge, in both East and West, is to become better known and respected. Europeans are generally unaware of its dynamic worldwide growth, the nature of its teachings, or the quality of life it offers.

In Western Europe, the Church is growing slowly, with the exception of its clear success in Portugal, but a process of consolidation appears to be taking place. Strong second-, third-, and even fourth-generation LDS families are appearing everywhere. Church members are taking advantage of expanded opportunities for education, especially higher education, and are thus better able to contribute to and benefit from the prosperity of Western Europe. European Latter-day Saints are sending out more of their own as missionaries than ever before, and two and three generations of indigenous leaders are heading the Church in Europe.

Finally, from an LDS point of view, Europe is still divided. The Western countries are awash in secularism, prosperity, and religious apathy that pose a major challenge for the Church to find new ways to gain the interest and respect of these secular societies. For Central and Eastern Europe, the new decade and the coming new century will undoubtedly see thousands of new LDS converts and congregations. Perhaps even as the people in these countries have brought a new inspiration of freedom and human rights to the West, they will also bring a new spirit of religious desire that will benefit the Church.

(See Basic Beliefs home page; Church Organization and Priesthood Authority home page; The Worldwide Church home page)

Illustrations

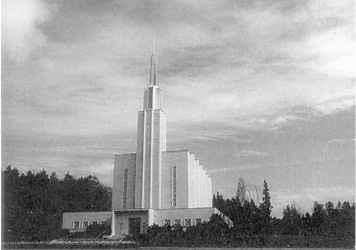

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Europe, including the British Isles and Scandinavia, as of January 1, 1991.

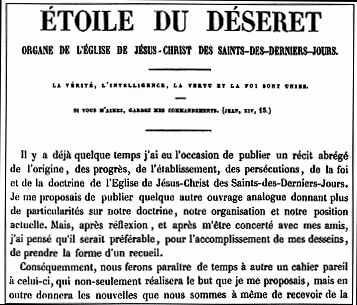

Elder John Taylor, one of the first LDS Missionaries in continental Europe, began the French publication Etoile du Deseret ("Star of Deseret"). Courtesy Rare Books and Manuscripts, Brigham Young University.

Leipzig Relief Society (1907). Many residents of eastern Germany joined the Church in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

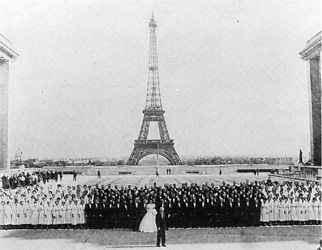

The Mormon Tabernacle Choir on world tour in Paris, 1955.

Bibliography

Babbel, Frederick W. On Wings of Faith. Salt Lake City, 1972.

"Encore of the Spirit," Ensign 21 (Oct. 1991): 32-53.

Sharffs, Gilbert W. Mormonism in Germany. Salt Lake City, 1970.

Encyclopedia of Mormonism, Vol. 1, Europe, The Church in

Copyright © 1992 by Macmillan Publishing Company

All About Mormons |

http://www.mormons.org |